While our focus is often on the prison era of the St Helena Penal Establishment from 1867, the previous 15 years saw St Helena Island used as a quarantine site. Moreton Bay settlement was opened up to free immigrants in 1842 and in doing so it became exposed to outbreaks of disease the immigrants brought with them on the ships. The story of these immigrant ships being temporarily stationed at St Helena Island contains some fascinating stories of people full of hope as they arrive in their new home. But these are also stories of despair, evidenced by the permanent reminders left behind on St Helena Island in the form of their graves.

I’ve written about some of these graves before, in previous blog posts ‘3 graves that can’t be found’ and also ‘5 graves that can’t be found.’ Back in 2018, I was only at the beginning of understanding what the full quarantine story was. The tour guides, educators and rangers conducting tours on St Helena had always known there was talk of ‘immigrant graves’ on St Helena Island, but how many, who they belonged to and exactly where they were located had never been certain. Since that time, conversations with Brisbane historian Liam Baker and his extensive research into his own family and into St Helena’s burials has uncovered so much more. And in the last few months, conversations with private individuals with ancestors who were on the immigrant ships has finally convinced me to finish what I started.

This blog post series will focus on the ships and immigrants known to have had a connection to St Helena Island from 1852 to 1866. I feel the stories may be even more poignant now, as all of us readers now have a new lived experience of quarantine and disease that has permanently shaped out perspective on the topic. We can’t help but feel empathy and connect on an emotional level to what plays out in the stories of new immigrant families, ready to start living, but instead being met with disease and death.

This series will provide details of a number of ship arrivals to St Helena Island and also how the immigrants utilized St Helena Island during their time of quarantine. Importantly, I will also give details gained from extensive research into 12 known immigrant deaths on board ships quarantined near St Helena Island and 10 known burials on St Helena Island, including 1 man, 3 women and 6 children.

Maria Soames, 1852

The 785-ton ship ‘Maria Soames’ left England on the 18th of February 1852 and arrived on the 4th July 1852. After a 116 day voyage, the 281 immigrants on board, (1) were looking forward to ending their long journey in Moreton Bay. However, the Captain overshot Brisbane and ended up at Fraser Island, only to be hit by storms, high seas and a damaged masts as it turned back. After days of stormy weather, the Maria Soames finally arrived in Moreton Bay. On board were the Goodwin family – Michael, 39 a labourer from Limerick, wife Johanna, and their sons John 18, Francis 14, Michael 10, William 7, Robert 1 and daughters Mary 16, Ellen 5 and Bridget 3. (2)

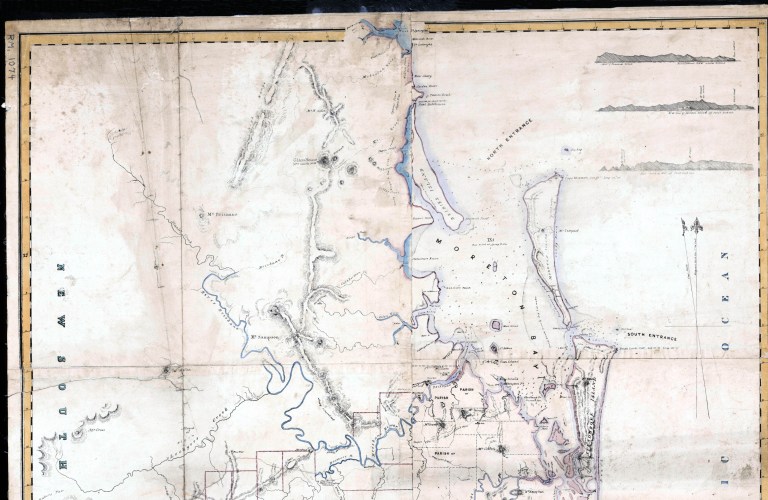

The Goodwin family are descendants of historian Liam Baker and Liam has supplied much of information I am recounting here in his own blog posts: ‘The tragic little burial ground that Moreton Bay never knew it had.’ Part 1 can be found here and Part 2 can be found here. For St Helena Island, this is the first ship that we definitively know stopped at St Helena Island and had someone alight from the ship and step onto St Helena. St Helena at this time was a rugged, wooded island, as shown in the watercolour image below from 1853. The sheltered harbour pictured below is the most likely place on St Helena for an immigrant ship to enter and remain for some time, and it is also the place that would allow access on to the land.

Johanna Goodwin and infant

On board the ‘Maria Soames,’ Johanna Goodwin had gone into labour ‘within sight of the Glasshouse Mountains.’ Given that the ship had been in the midst of terrible weather, with storms buffeting the ship, one can only imagine how that would be for a heavily pregnant lady. The ship finally anchored temporarily near Moreton Island, but Johanna and the child both died during the birth. It was St Helena Island that provided the opportunity and access for a hasty burial of Johanna and her infant, even before the authorities had boarded the ship for inspections (2). Proof of this comes from Reverend Henry Berkeley Jones, in his book ‘Adventures in Australia in 1852 and 1853,’ who noted:

“There we interred a poor emigrant and her infant child, who died just as she had completed her voyage, leaving her husband the guardian of ten surviving children – a heavy charge and drawback to this poor man, who was a peaceable, well conducted Irishman.” (2)

The remaining Goodwin family settled in Queensland and began to rebuild their lives. Eldest son John, 18 years old on arrival, joined the Customs department in 1854, working in Brisbane and Maryborough for his entire career. It was said that there was ‘no more familiar figure along the wharves than he.‘ In one of the loveliest ironies, John Goodwin ‘was the first man to light the Cape Moreton light, and he formed one of the party that first beaconed and buoyed the Sandy Straits and Mary River about the year 1860.’ (3) How ironic that he was to return to Fraser Island and Moreton Island years later in entirely different circumstances, helping to guild ships and their passengers safely into harbour.

It was another 10 years before the next immigrants set foot on St Helena Island, and while time had gone by, the circumstances remained the same. More on that in the next blog post.

Sources:

- Moreton Bay Courier (Brisbane, Qld. : 1846 – 1861), Saturday 10 July 1852, page 2

- Liam Baker ‘The Haunts of Brisbane.’

- Find-A-Grave